Living through COVID-19 in Australia

August 24, 2021

By Chris Oestereich

During a recent call with the End Coronavirus team, Emergency Doctor Noor Bari, MBBS BSc. shared the story of the pandemic in Australia. Her tale was quite different from what I thought I had pieced together from international news reports, so I asked if she would take part in an interview to help others see Australia’s experience with COVID-19 through her eyes. Along with sharing her story, Dr. Noor also provided a number of references that are included throughout the text.

The interview text has been lightly edited.

CO: What were the circumstances like in Australia at the outset of the pandemic when the world was watching Wuhan?

NB: It was a really hard time in Australia. Much of the bushland was on fire and the air was thick with smoke. The debate of surgical masks vs respirators was already in the public consciousness, as people were struggling to cope with the poor air quality and wearing various masks to try to get by. It was during this time of bushfire that I stocked up on a couple of respirators. The firefighters were using them then, and there were already murmurings of shortages, with workers finding the smoke-clogged masks difficult and replacing them problematic.

In the New Year, the TV started to report the unusual cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, and then the images of overcrowded hospitals and deserted streets. In Australia, I noticed that the supply of respirators in our local hardware store had gone, although people were not wearing them in Australia. Later I discovered that they had been sent by well-meaning Australians back to China to help HCW with the outbreak.

CO: When you had your first cases, how did the nation respond? Who was aligned on the need for rigorous public health measures and who was against them?

NB: Slowly over time Australians watched the outbreak develop in Italy. Still very little had changed in Australia at that time. A warning not to travel to the outbreak zone was issued at the end of January as the first case in Australia was identified.

There were a few cases that came into Australia from overseas sporadically during this time. As is the nature of the older strains of SARS-CoV-2 many of these did not cause widespread outbreaks.

In those early days, there was not really a clear intent to eliminate COVID-19. Public health departments, such as they were, tried to swing into action but they were hampered by many things.

First among those was a poor understanding of this new disease. We did not yet understand the extent of asymptomatic cases or presymptomatic transmission.

The symptoms were not well known either. Although there is published work on other coronaviruses causing a wide variety of symptoms, initially only very narrow criteria were established to detect cases. Fever, cough, sore throat, and shortness of breath were amongst the symptoms identified. We had not yet realised patients could be afebrile (lacking a fever), asymptomatic, have GI symptoms, anosmia (partial or total loss of the sense of smell), and many other symptoms. We also had not realised how children could have coronavirus with very few signs or symptoms.

Testing was also a challenge due to false negatives.

The second issue that made it difficult was that the airborne part of the pandemic plan (for influenza and influenza like illness/TB/measles etc.) was activated and then the decision was reversed. The WHO gave out advice that changed from airborne to not airborne in less than 24 hours, and this meant that guidelines in Australia changed just as fast. This made it harder to control outbreaks as we no longer had the tools to stop transmission.That meant that many things from school closures, to what type of PPE to use, had to be re-established over time as evidence was gathered. The precautionary principle and the decades of evidence of aerosol and airborne spread of other coronaviruses was lost.

CO: How did things play out in the early going? Where were there successes and how did that affect the approach in other areas?

NB: By the first few weeks of March the case numbers in the UK and US started to climb. One of the key steps taken was the closure of international borders. This did not occur until 20th March 2020.

Unfortunately, almost at exactly the same time as the borders were closed, an outbreak was sparked by the docking of the Ruby Princess ship.

As hospitals started to come under pressure in many other countries, Australia attacked the problem of COVID-19 with a renewed sense of purpose. Test, trace, and isolate efforts were ramped up in all six states. The community participated in public health measures with reasonable success. Financial aid was established via the “jobkeeper” program, business support packages, mortgage, and rent relief, etc. which helped people to get through the national “lockdown”. Further payments were made to support people that were instructed to isolate due to being COVID positive. Later, support was also given to close contacts that were isolating on public health instructions.

There were many stumbles and mistakes along the way. Cases missed and then found. Incursions into healthcare, schools, etc.

Initially, people returning to Australia from areas with coronavirus outbreaks overseas were advised to self isolate for 14 days at home. Unfortunately this proved to be difficult for many reasons and breaches of community quarantine occurred. This practical difficulty led to the set up of the hotel quarantine system.

Hotel quarantine worked reasonably well until B117 [Alpha] emerged, at which point regular breaches started to occur that only worsened in frequency with B1617.2 [Delta]. Again, we were having problems due to that lack of recognition of the role aerosol plays in transmission.

There were also challenges with repatriation. The process was opaque and appeared to be inequitable. Stories of extortionate airfares, and persons stranded for many months were common, while on the other hand high profile persons and sports persons appeared to have no problems.

CO: What was the general outlook towards public health measures and the aim of eliminating COVID during the time when Australia had eliminated transmission?

NB: New Zealand declared from the outset that they would try to eliminate COVID-19. This immediately set the bar very high for the whole region, which was a very good thing for the island communities as well as Australia. Although Australia did not set the same target at a government level, certainly the idea of fighting COVID-19 instead of just letting it circulate was firmly embedded in the public mind, and in the public health effort.

The only state in 2020 to deliberately target zero COVID-19 cases was Victoria. It was a controversial move to keep the state in a 112-day lockdown until a target of zero community cases. Professor Allen Cheng designed the exit strategy model for Victoria, and very controversially recommended getting to zero covid. All other states simply got their heads down and did normal public health work and celebrated achieving zero cases as a nice but unexpected reward for their hard work.

Throughout this fight to survive, the federal government and many respected doctors argued that eliminating COVID-19 was impossible, and dangerous even. This war of words raged in the newspapers, and made it very hard for people in Victoria, the hardest-hit state. The most vocal of these voices were Dr. Nick Coatsworth, the Deputy Chief Medical Officer of the Australian government (now resigned), Dr. Brenden Murphy, then Chief Medical Officerand current Secretary of State for Health, and Prime Minister Scott Morrison.

The NSW Government team (Premier Gladys Berejiklian, Health Minister Brad Hazzard, and Chief Health Officer Kerry Chant.) while not promoting the circulation of COVID-19 still tried to strike a balance between circulating COVID-19 cases and economic activity. Although they aimed to pursue such an approach, other states did not want to risk incursions of COVID-19 and closed their borders. NSW was an outlier in this respect and the state was excluded from travel bubbles with New Zealand and the other Australian states.

Many say an interview with PM Scott Morrison and related comments pressured NSW to live with the virus, rather than lockdown, and led to the current disaster with the delta variant outbreak. In the interview, Morrison claimed the problem with an elimination strategy was that “all you need is one outbreak and it rushes through your community very quickly because people become even more complacent, and so it is a very risky strategy and one that can be very illusory.”

(CO: As Dr. Noor shared, the Australian Finacial Review (AFR) published an editorial on September 8, 2020, claiming that “aggressive suppression” efforts were “extending false hope to lockdown-fatigued Victorians about life, work, and business being back to normal by Christmas.” Australia was experiencing a steep decline in cases at the time, with a 7-day average of 79 cases. The 7-day average stayed below that figure for the next ten months, while largely staying below 30.)

The real effort to target zero started in NSW Australia when in September last year we had a short run of zero cases in the community. People felt relaxed about going to restaurants, cafes and gyms again. Domestic business began to recover.

Subsequent outbreaks over Christmas were handled with far more determination and a clear endpoint of zero COVID.

CO: How did communities react when COVID was reintroduced? What about various levels of government?

NB: It’s very hard to speak for the community because there are so many people impacted in so many different ways by COVID-19 and the lockdown.

The biggest and most commonly held reaction has been anger at the lack of preparedness on the vaccination front. Initially, Australia invested heavily in only one vaccine as two of the other candidates failed development and the fourth was only bought in small amounts as a backup supply. The chosen vaccine then became subject to limitations due to a rare side effect. The difficulties with dealing with such a rare but serious side effect in a low COVID-19 prevalence country led to changes in guidance that were communicated poorly. The whole process took time and damaged trust.

The second biggest source of anger is the failure of the quarantine system due to a failure to implement airborne disease control measures. At the time the airport driver became infected, there was no compulsion for him to wear a respirator or be vaccinated.

People are hurting in many ways. Young essential workers that were never eligible for vaccination due to their age have been heavily impacted and admitted to hospital and ICU. Lives are being lost, including young lives. Jobs have been put on the line, or lost. Domestic air travel is once again on government support. Incomes were heavily impacted and government support packages that were prematurely ended in March 2021 were slow to be redesigned and redeployed.

Unfortunately, Australia was quite lazy during its zero COVID time.

It is not just the lack of progress in vaccinations that has been an issue. Governments have made no progress in ventilation and engineering mitigations. Community respirator use has not been encouraged and the community education required for this has also not been done. There has been no work or acknowledgment of the benefits of HEPA filtration. No extra quarantine has been built and made available as yet.

This means that Australia remains unable to repatriate citizens in an emergency and unable to control outbreaks that are now spreading faster than ever.

When we should have been preparing for the storm we always knew would be coming, we did nothing. Transmission gains were an entirely predictable pathway of evolution. We neither built the quarantine to deal with this, established the protocols for airborne disease control, nor vaccinated the population to protect them in case of an accident.

***

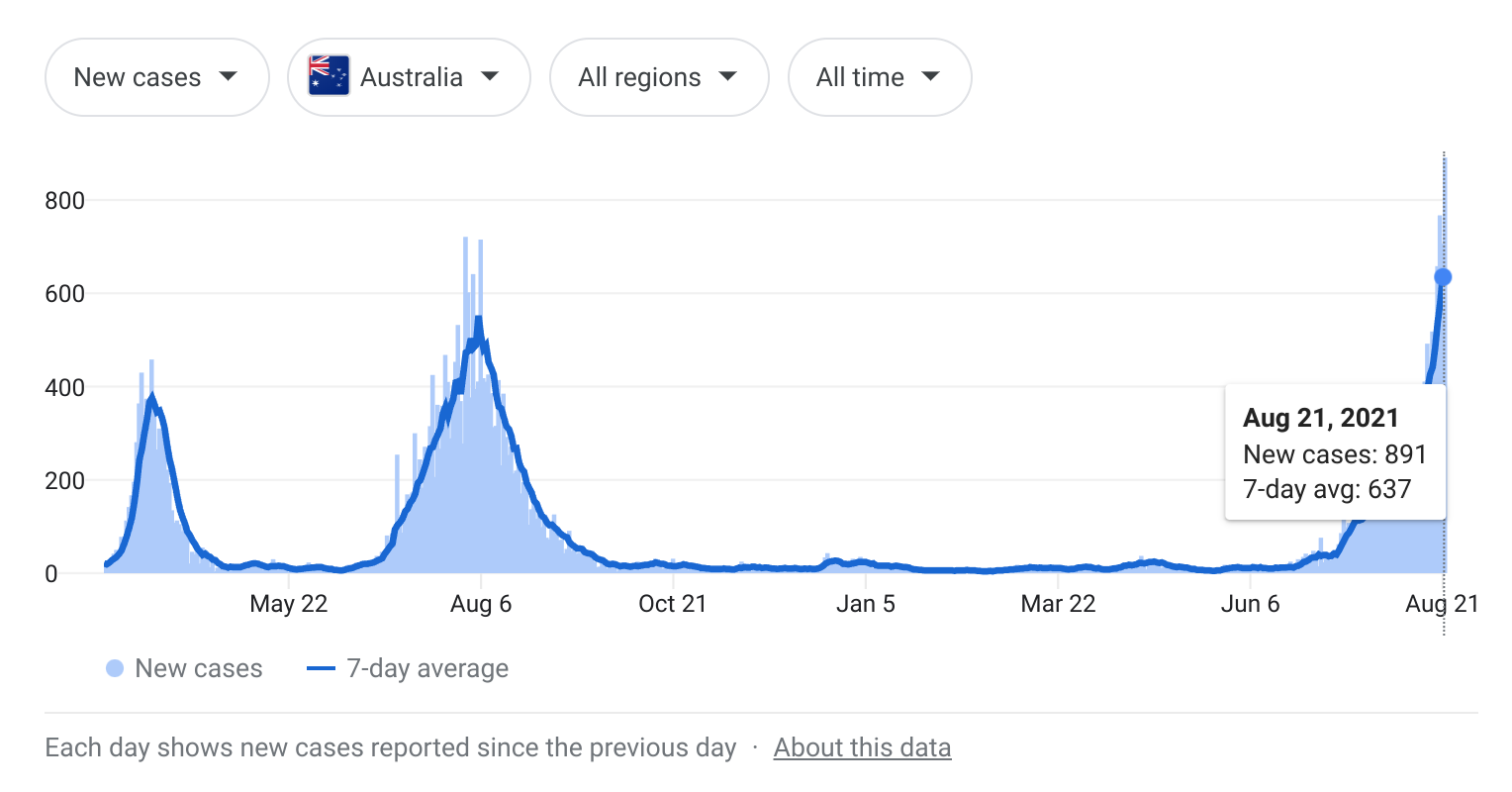

CO: I thought I’d share a brief synopsis of the current state of the pandemic in Australia. The two graphs below will give you the big picture. While Australia had 891 positive cases on August 21, New South Wales accounted for 822 of those cases.

NSW went into lockdown on August 14 as the Australian Medical Association announced that the healthcare system in NSW could “no longer manage” the swelling caseload. Fines of $5,000 were put into place as they looked to keep people from violating lockdown protocols. NSW premier, Gladys Berejiklian, announced that the state was aiming to have 70% of adults fully vaccinated by the end of October and that the goal was to hit 80% by mid-November.

While those vaccination goals are desirable, Berejiklian has recently been rebuked for suggesting the state could begin to ease restrictions once vaccination rates hit 50-60%. NSW’s daily case numbers are essentially vertical, with the 7-day average rising from single digits in mid-June to 637 on August 21. The other five Australian states have done far better collectively in limiting transmission, but their numbers are now slowly rising as NSW’s circumstances spin out of control. These circumstances suggest the need for nations to have a shared commitment to the elimination of the virus, especially when the population is largely unvaccinated, and that this goal needs to be pursued without hesitation. Attempts to minimize transmission control efforts (including failure to deploy airborne disease transmission mitigation specifically) with the highly contagious Delta virus should be viewed as dangerous failures of leadership.